Plague! - Exploring St Davids Cathedral Library

For Libraries Week 2020, Dr Heather Payne - Llandaff Elected Lay Member of Governing Body - reviews materials on Bubonic plague at St David's Cathedral Library in light of COVID-19:

The Coronavirus pandemic of 2020 is in many ways like the great Plague of London. Then, Bubonic plague spread around the world in numerous waves, killing many. We now know that plague was a bacterial infection transmitted by fleas carried on ships’ rats, but the existence of ‘germs’ spreading disease was unknown until 1880. Until then, the prevailing theory was that ‘miasma’ or poisoned air, caused illnesses.

Just like today, the spread of infections was studied carefully by Doctors, and the first to suggest they could be spread by touch, was Dr Richard Mead (1673-1754), physician to Queen Anne. His book[1] on ‘Pestilential Contagion’ published 300 years ago in 1720, was a careful study of the way that Bubonic plague had spread since 1665 from London across Britain in a series of waves. St Davids Cathedral library has a copy of this work, which I was delighted to review, along with Mead’s ‘Medica Sacra’[2] and Risdon Bennet’s ‘Diseases of the bible’[3] for Libraries Week 2020 [see below].

[1] Dr Richard Mead (1720) A Short Discourse concerning Pestilential Contagion, and the Method to be used to prevent it

[2] Dr Richard Mead (1754) Medica Sacra

[3] Risdon Bennet (1887) Diseases of the Bible

Many of the important factors we now take as essential to combat coronavirus are found in Dr Mead’s book. His advice was used by Government to pass the first ‘Quarantine Act’ in 1720, due to concern that an outbreak of Plague in Marseille threatened to spread to Britain. Dr Mead cautioned

‘in two parts : The preventing its being brought into our Island; And, if such a Calamity should happen, The putting a stop to its spreading among us.’

He recommended a 40 day quarantine in a Lazaretto (isolation hospital) for anyone coming to Britain – this echoes our travel bridges and 14 day self isolation rules for coronavirus.

Dr Mead also warned about the possibility of infection from fabrics, clothing or animal skins- items that could carry ‘contagion’ through handling them. This principle applies to coronavirus, requiring scrupulous surface hygiene. Dr Mead recommended washing with vinegar and water, which would have been an effective antiseptic, a precursor of our hand sanitiser. He also emphasises the importance of isolation of affected families, to avoid spreading disease, although their measures were rather more drastic even than our coronavirus regulations are at present:

‘The main Import of the Orders issued out at these Times was, As soon as it was found, that any House was infected, to keep it shut up, with a large red Cross, and Lord have Mercy upon us on the Door; and Watchmen attending Day and Night to prevent any one's going in or out, except Physicians, Surgeons, Apothecaries, Nurses, Searchers, &c. allowed by Authority: And this to continue at least a Month after all the Family was dead or recovered*

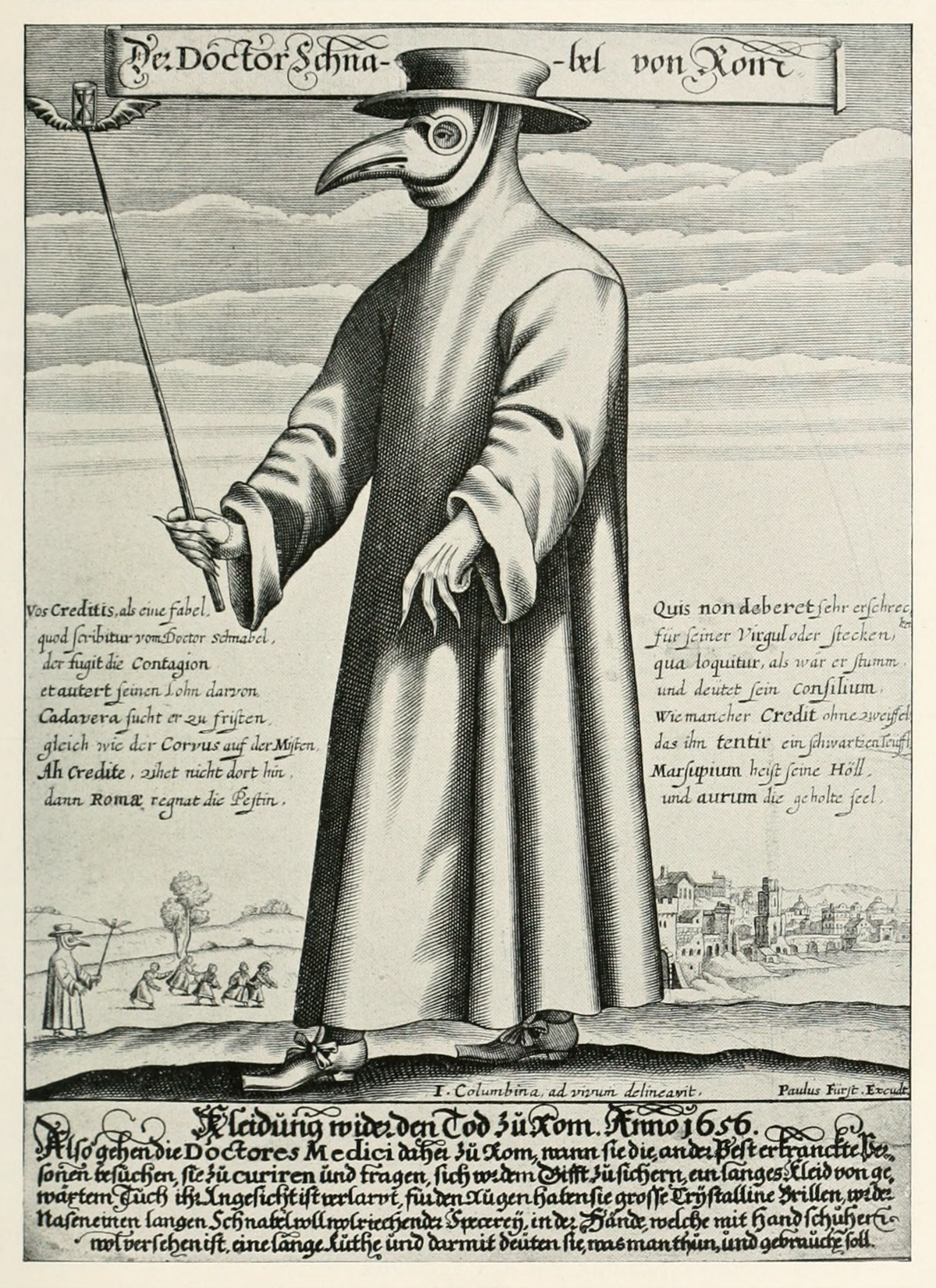

Even so, Dr Mead’s principle of prevention still holds good, our mainstay of controlling coronavirus being social distancing, isolation, handwashing, and also wearing face coverings. The main components are seen in the well known ‘Plague Doctor’ costume dates from the 17th century, and Dr Mead recommends its components, which we would now recognise as ‘Personal Protective Equipment’ or PPE.

The beaked mask (filled with straw and fragrant herbs) is a prototype face covering, to prevent the Doctor being exposed to what we would now call droplet or aerosol spread, and also includes spectacles. Sadly, some eye specialists were early coronavirus victims, before it was realised that droplet spread through the eyes was important- health care workers now routinely use eye protection. The all- covering , oilskin hooded gown and hat is equivalent to today’s fluid repellent gown. The ensemble is completed by gloves, and a long wand, which would permit examination of the patient without touching – now recognised as social distancing.

The other Mead and the Risdon Bennet books go on to explore diseases in the bible, and the nature of ‘plague’ as literally a ‘smiting’ or punishment for misalignment with God’s will, along with the redemption and healing manifested in the person of Jesus. We certainly have other explanations for illness these days, but there is still a great need for healing of all affected physically, mentally and socially by this cpronavirus ‘syndemic’ – a pandemic superimposed on structural inequalities, harming the most vulnerable in society.

We have been describing this time as ‘unprecedented’. These treasures found in St David’s Cathedral Library tell us that maybe it’s not, and remind us of how much we have forgotten and need to rediscover.