The resurrection offers a compassionate response to global migration

Acts 10: 34-43 | 1 Corinthians 15: 19-26 | Luke 24:1-12

Risen Lord, give us a heart for simple things. Love, laughter, bread, wine and dreams. Fill us with green growing hope, and make us an Easter people whose song is Alleluia, whose sign is peace, and whose name is love.

I’ve got for you a rather sombre story on this joyful and wonderful Christian day. It’s a reminder that there’s nothing glib about the message of resurrection hope. I tell it because our hearts and minds are focused on the war in Ukraine and on what is a compassionate response to global migration.

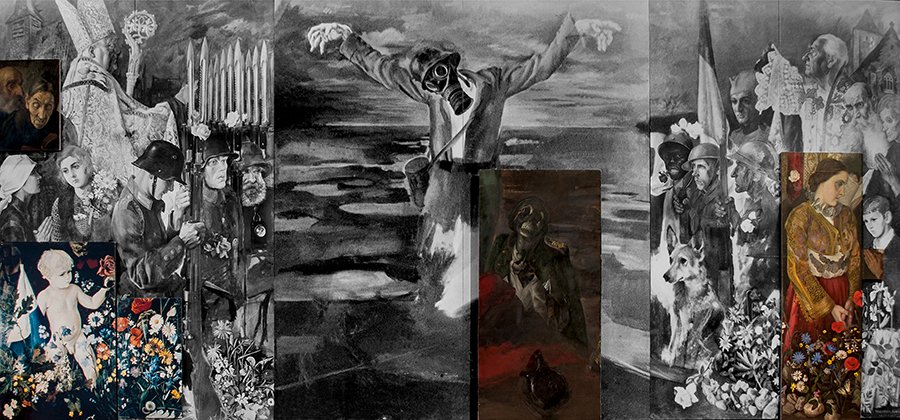

It's a story primarily about a work of art: brought to my attention by Neil McGregor and an exhibition which happened at Leicester City Museum about a decade ago, which highlighted the work of Johannes Matthaeus Koelz.

Koelz was a skilled artist. Brought up a Roman Catholic in Bavaria, between Munich and Salzburg, he was expecting to attend Munich’s Fine Arts Academy. But just after his 19th birthday, in 1914, his brother was killed in action in the early days of the First World War.

Johannes himself then joined the Bavarian Infantry and headed for the Western Front where he later earned himself the Iron Cross for valour. He rescued a comrade from behind enemy lines, undoubtedly saving his life, and was commended for immense bravery under fire.

Our hearts and minds are focused on the war in Ukraine and on what is a compassionate response to global migration.

Following the end of the war he combined his studies at the Academy with a career in the police force. Clearly the experience of war had cultivated in him an anti-militarism and over the first seven years of the 1930’s he worked on a piece of church art which expressed his loathing of war.

It was a triptych, three panels, the like of which you would find in many churches or cathedrals, sitting behind the high altar and so defining the context where the eucharist is celebrated. The central image of Koelz’ triptych is, not surprisingly, a crucifixion, and on either side there are figures praying, as it were at the foot of the cross.

Yet this work of art is shocking because the figure being crucified is dressed as a German soldier captured on a barbed wire fence, his face covered with a gas mask and close by, in the landscape of Calvary there is another dead soldier, killed in battle. Those praying are also soldiers, on the left Germans and on the right Allied troops, praying, we assume, to the same God and presumably praying for the same peace. Most discomforting of all are the figures of bishops and priests blessing the weaponry of war on both sides.

You can tell it's a challenging work and there are few images of hope within it. Indeed, if it were part of this Cathedral church I’d be looking at it, wondering where resurrection was being proclaimed. As it is, it’s unlikely to ever adorn any Christian church or even a museum because after painstakingly constructing it over several years Koelz used the village sawmill to cut it into 16 or 20 pieces, and distributed them around trusted family and friends. I’ll tell you why he did that in a moment but let’s just acknowledge what ‘Thou Shalt Not Kill’ – for that’s the title of Koelz’ triptych – what it reinforces on this Easter Day.

I’m sure you’re aware that the stories of the resurrection in all four gospel accounts differ from one another. Different people, different sequences of events, differing reactions and time frames within which Jesus appears back from the dead. But the one thing they all have in common is that the conviction that he has been raised begins at a tomb. Indeed, the emptiness of the tomb was itself enough to convince some of the disciples of the reality of the resurrection.

When we heard, just now in Luke’s account, that Mary Magdalene, Joanna and another Mary go to the tomb this isn’t just about locating the action. Tombs are symbols to us, places of death and desolation and abandonment.

Indeed, one of the texts I had early this morning sent a photo of the sun rising over tombs in a graveyard. Easter Day dawning over a place which speaks of the cruelty of life and of the brutality of grief. Koelz’ loathing of war was born when he saw the destruction of life in the trenches. There he met the horrors of death. As Paul says in his letter to the Corinthians ‘the last enemy to be destroyed is death’.

Without God’s action which we celebrate in this service and enact week on week in the Eucharist, there’s no answer to death, no rescue from the tomb. In the triptych, there were flowers, country people, and beautiful praying hands but overall it seems to say that war – and all that destroys life for us, all that takes away our freedoms - that such darkness has won the day.

Koelz has no sympathy at all for Hitler’s populism.

But. And here’s where Koelz’ own life tells a remarkable story. Into that horror of death resurrection intrudes.

It’s 1936. Koelz has been secretly working on his anti-war triptych, knowing that it was a dangerous work for anyone to view. The government of National Socialism has been in power for three years and Koelz has no sympathy at all for Hitler’s populism.

Yet it seems that someone knows of his talent and he is approached, asked if he will paint Adolf Hitler’s portrait. He’s offered eight sittings with the Fuhrer and an eye-watering fee for the commission. On one condition, that he wears the brown shirt of the Nazi Party whilst he is in Herr Hitler’s presence. We’re almost certain that he refuses the invitation, though just in the last few years, I think as a result of the research done for the Leicester exhibition, a drawing of Hitler by Koelz has come to light, so maybe he did meet him.

What we do know is that almost immediately two things happen. Koelz goes to the sawmill and chops up ‘Thou Shalt Not Kill’ ready to carry some of the fragments out of Germany to a safe haven. However, before he can leave an arrest warrant is issued charging him with supporting pacifist propaganda and a group of military police or the like come to arrest him. Astonishingly the person in charge of this arresting party turns out to be the very man whom Koelz had rescued, the act which had won for him the Iron Cross. And in that moment the man who owed his life to Johannes Koelz makes an important decision.

He tells the Koelz family that the arrest warrant is due to come into effect two days later. He goes back to his office and puts the document into his desk drawer for 48 hours. When he returns not surprisingly the Koelz family have fled, seeking asylum they eventually live the remainder of their life in Cork in Ireland. Six portions of the triptych have come to light but who knows if we will ever see the remainder of them.

God speaks to us of victory, of love, and life and liberty, of bread, wine and dreams.

Resurrection begins with a tomb. The dark realities of human misery, the enemies with which we contest, which Koelz tried to pour out in his painting of ‘Thou Shalt Not Kill’. But today we cry Alleluia that it does not end there. God speaks to us of victory, of love, and life and liberty, of bread, wine and dreams.

Some of you helped me send a message of solidarity to Ukraine last Sunday when an interreligious visit was happening there. The Jewish Rabbi who organized it later sent greetings back to us in Llandaff saying this,

’Easter is, after all about the life coming from death, light coming from darkness. And this is what we tried to offer the refugees we visited and the people of Ukraine at large… Let our prayers be for the victory of good and the triumph of light. This year, perhaps more so than on many others, the meaning of Easter seems to play out on the global stage even more than in the interiority of our hearts.’

He ends by saying ‘May we all be instruments for the light and for the good. Happy Easter.’

And that surely captures the reality of resurrection which Koelz experienced in that single decision made by the man he had previously saved. We all make decisions every day which bring life or death, light or darkness, grace and truth, or discouragement and despair.

The meaning of Easter seems to play out on the global stage even more than in the interiority of our hearts.

Luke says that when offered the hope of resurrection some of the disciples just thought it ‘an idle tale’ and did not believe the women. Others had their lives utterly transformed. Which is it going to be?

Is our song going to be ‘Allelluia!’ as we determine to live with grateful and generous hearts?

Is our sign going to be peace even when we’re wounded and betrayed?

Is our name love, with love we meet every tomb, every fear and threat to our freedoms.

We are Easter people and we have a risen Lord who longs to fill us with green growing hope. Alleluia!